Love Never Dies

“Love never dies.”—1 Corinthians 13:8.

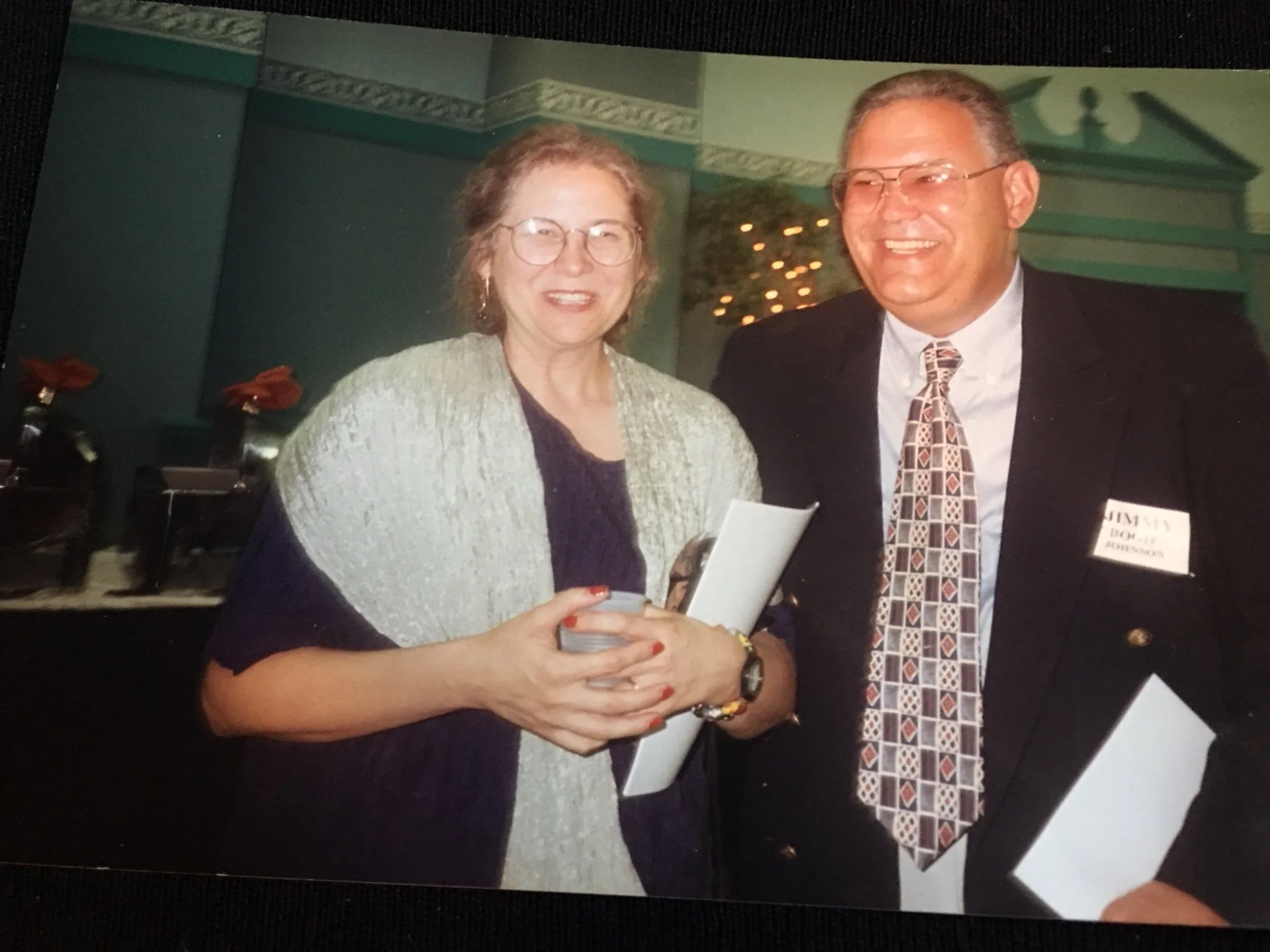

friends from our congregation who have died

I have heard this passage from 1 Corinthians about love many times, but when I heard it recently, directly from our friend Paul and our preacher Michael McCain, I was moved to tears. I have told grieving people that their love for and from their loved ones is still there and never dies.

I don’t understand it. It is a mystery. I look at pictures of my loved ones who have died, my brother and my grandparents, and I can feel their love as I send it to them.

Frederick Buechner and Henri Nouwen tell us that our bodies die, but our mutual love somehow returns to God and is kept for all eternity.

If you are a mystic, you have no difficulty understanding this. However, this may be a difficult concept if you are a person who comprehends mainly by rational thinking.

Why did this passage move me that Sunday? As I grow older, I have obsessed with how I will miss friends and family members when death separates us. Yet, I suddenly know in my heart that our love for each other will always endure.

Our love for them is ongoing, as is their love for us. We will never be lonely. I believe that in some mysterious way, this love never dies and is carried forward in eternity to be a transforming effect in ourselves, in them, and in the universe.

Today, I am thinking of the love of friends who have died: my younger brother, Jimmy, and recent friends, Phyllis, Kay, Hap, Rosemary, Pat, and Karen.

my brother