Surrender

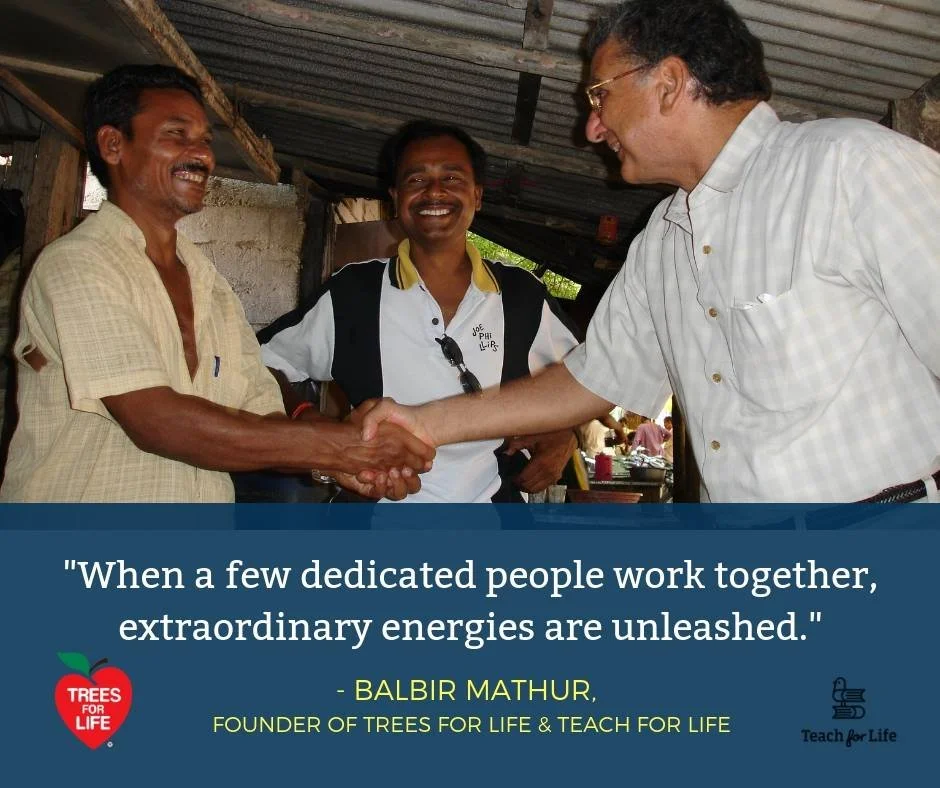

“The boat I travel in is called Surrender. My two oars are instant forgiveness and gratitude—complete gratitude for the gift of life. I am thankful for the experience of this life, for the opportunity to dance. I get angry, I get mad, but as soon as I remind myself to put my oars in the water, I forgive.”—Balbir Mathur,—Heron Dance interview (Issue 11).

As president of Trees for Life, Balbir Mathur planted 200 million morning trees in developing countries for 30 years. I thank the daily words from Inward Outward from the Church of the Saviour in Washington for introducing him to me.

Mathur’s extraordinary life is a story of constant surrender: immigrating to Wichita from India with no family contacts, mowing lawns, becoming world-known in business, developing a mysterious illness, leaving his business career, and starting an international nonprofit to plant trees in developing countries. The morning trees survive in dry conditions. Their leaves are nutritious in vitamins A and C and calcium; their seeds are used to purify water.

Mathur’s words are indeed words of peace that I hear in many disciplines across all religious barriers. When I can forgive, when I am filled with gratitude, I stay out of trouble and find peace. What an image.

We are in a boat called Surrender, and our two oars are gratitude and forgiveness, which keep that boat moving on course. I can imagine rowing on a river, not too big of a river and not too big of a boat. I will need other passengers who can take over the oars when I become too tired, who will read to me and let me rest or just allow me to soak in the scenery. And I will do the same for them.

Rick Plumlee, The Wichita Eagle, May 10, 2014.

Joanna https://www.joannaseibert.com/