Psalm 23 and Who Are the Shepherds?

“The Lord is my shepherd.”—Psalm 23.

Malinda Elizabeth Berry reminds us in an article, “Who Is My Shepherd?” on ChristianCentury.org (July 19, 2018), of a common misconception about the gender of shepherds. In biblical times, young girls were often shepherds, as were boys and men. For example, Berry reminds us that beautiful Rachel was tending her father Laban’s sheep when Jacob first saw her and fell in love with her (Genesis 29:9-10). Likewise, Zipporah and her sisters were trying to water their father’s sheep when Moses drove away some other shepherds bothering them (Exodus 2:16-17).

We may also infer that these young, fair maidens were just as masterful with a slingshot as young David!

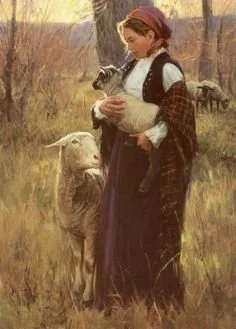

Berry asks us if we have seen Bible story pictures or paintings with girls as shepherds. Indeed, I could only find a few, including one by Hungarian painter Marko Andrea (1887) called Shepherd Girl. Berry then challenges us to consider having girls and boys dress up as shepherds in this year’s Christmas pageant! (At our staff meeting, Luke, our Family Ministries Coordinator at St. Mark’s, reminded me that, unknown to me, St. Mark’s has been including girl shepherds for years!)

This is another example of a tradition that doesn’t align with historical facts: that shepherds should only be boys or men. It makes me wonder why I didn’t think of girls as shepherds, even after reading the stories of Rachel and Zipporah more times than I can remember. Now, it is so apparent.

I hope you can share my excitement about Berry’s new insights into stories we thought we knew so well. Berry’s thoughts remind us not to gloss over old Bible stories, but to hope to see new insights each time we read them. They also encourage us to continue researching what others are discovering in their study of the Bible. Finally, it reminds us that the Holy Spirit is alive and well, and continually teaches us new insights from old stories.

Joanna. https://www.joannaseibert.com/