A Senility Picaresque

Guest Writer: Ken Fellows

Remembering Monhegan Island

Well into the 8th decade, my creeping forgetfulness of people and place names is disturbing. Memory lapses derail and complicate conversations, writing, and even daydreaming. In medical school many years ago, Alzheimer’s Disease was taught to be the early-onset dementia at the age of 40-50 of dementia. No longer --- memory loss, disorientation, general confusion, and other symptoms are all named “Alzheimer’s” whether the afflicted are in their 40s or their 90s.

The first signs of senility began several years ago, when I, in the midst of relating facts or telling a story, suddenly couldn’t recall a vital name or a key event. To cover my deficit, I began using the tactic elderly writer Roger Angel once recommended: “I send an Indian scout into the unspoken next sentence to warn of missing names or items --- and modify or change my words to avoid the impending deficiency.” Alzheimer’s runs in families, and my father suffered progressive dementia, finally requiring hospice care. There is reason for my concern.

The novel Still Alice is a brilliant description authored by neuroscientist Lisa Genova. She realistically and artfully describes the fictional progress of a 50-year-old Harvard Professor woman who progresses through all the stages of Alzheimer’s disease, showing its effects on her profession, her family, and her self-esteem. I recently chose to reread the book, hoping for some insight.

In the book, Alice had been barely, but bravely, adjusting to her progressive dementia for a decade when she was persuaded to attend a Harvard Graduation Ceremony. The event’s featured speaker, a Spanish actor, talked about his life’s adventure-- what he called a “picaresque … a long journey that teaches the hero lessons learned along the way.” He offered a requisite five goals: “Be creative, be useful, be practical, be generous, and finish big.” Alice, in the book, reflects on that advice, but doesn’t comment on an obvious concern: how could anyone in the throes of dementia ever hope to “finish big?”

That admonition ”to finish big” was puzzling and distracting for me. What might that entail, and how might it be accomplished in anyone’s life afflicted by Alzheimer’s disease? The usual slow but progressive drift into senescence would seem to make finishing strong a remote consideration.

Still perturbed days later, I continued reading, hoping an answer to my consternation would be offered. Instead, quite providentially, an answer literally fell out of the book. It was a newspaper clipping I had left in the back pages during a previous reading of the book years before. The short article “The Joy of Taking the Family to Dinner” was authored by psychiatrist and long-time Boston Globe contributor Elissa Ely. In the piece, she described family dinners with a friend’s octogenarian father, who was severely afflicted with Alzheimer’s and no longer verbal, who consistently became agitated at the end of family meals in his care facility:

“Whenever the family eats with him, my friend’s father picks up the tab that does not exist. He signs on a napkin or a scrap of paper someone remembers to bring, or on other receipts, conveniently pulled from a pocket. I don’t know if the writing is legible or if he can read the name he signs. But he signs with

finality and satisfaction. The very action makes him content. He is taking his family to dinner.”

So there it was, ---the answer I sought. Despite being lost in the fog of dementia, and near the end of his life’s adventure –his own picaresque –the father had found a way to “finish big.”

It also became evident that I had noted this remarkable lesson years ago and saved the article … but had forgotten.

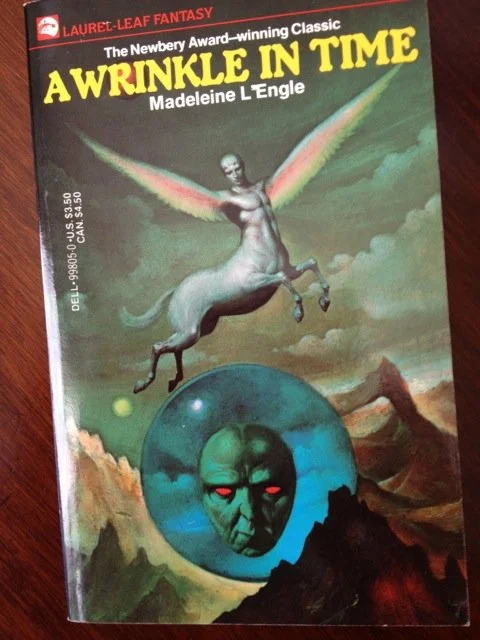

I have painted on Monhegan Island in the summer for about 15 years, usually in a realistic style. Last year, I had an impulse to paint a section of the Monhegan Harbor shoreline and its houses in a semi-abstract way. It occurred to me that the painting could be a metaphor for memory loss.

Ken Fellows

Joanna joannaseibert.com https://www.joannaseibert.com/