Benedictine Life

“Listen carefully, my child, to my instructions, and attend to them with the ear of your heart.”— Prologue to Rule of Benedict.

In the 6th century, Benedict of Nursia tried to follow a spiritual path on his own and realized he had to do so in community. From his awareness, we now have the Rule of Benedict, a way to find and follow God in community, balancing work, study, sleep, worship, prayer, and recreation. Members of Benedictine monasteries have used this rule for centuries.

Today, people are developing ways to follow a rule as they live in the secular world, still connecting in community with spiritual friends and spiritual directors.

This prologue to the rule is my favorite part. “Listen with the ear of your heart.” This is the call to the spiritual life, a way to live in the world still connected to God. First, we are to listen and pay attention. We are to use the ear of our hearts. We are to connect to something outside ourselves, hearing and loving. We hear about and learn from love in a community outside ourselves.

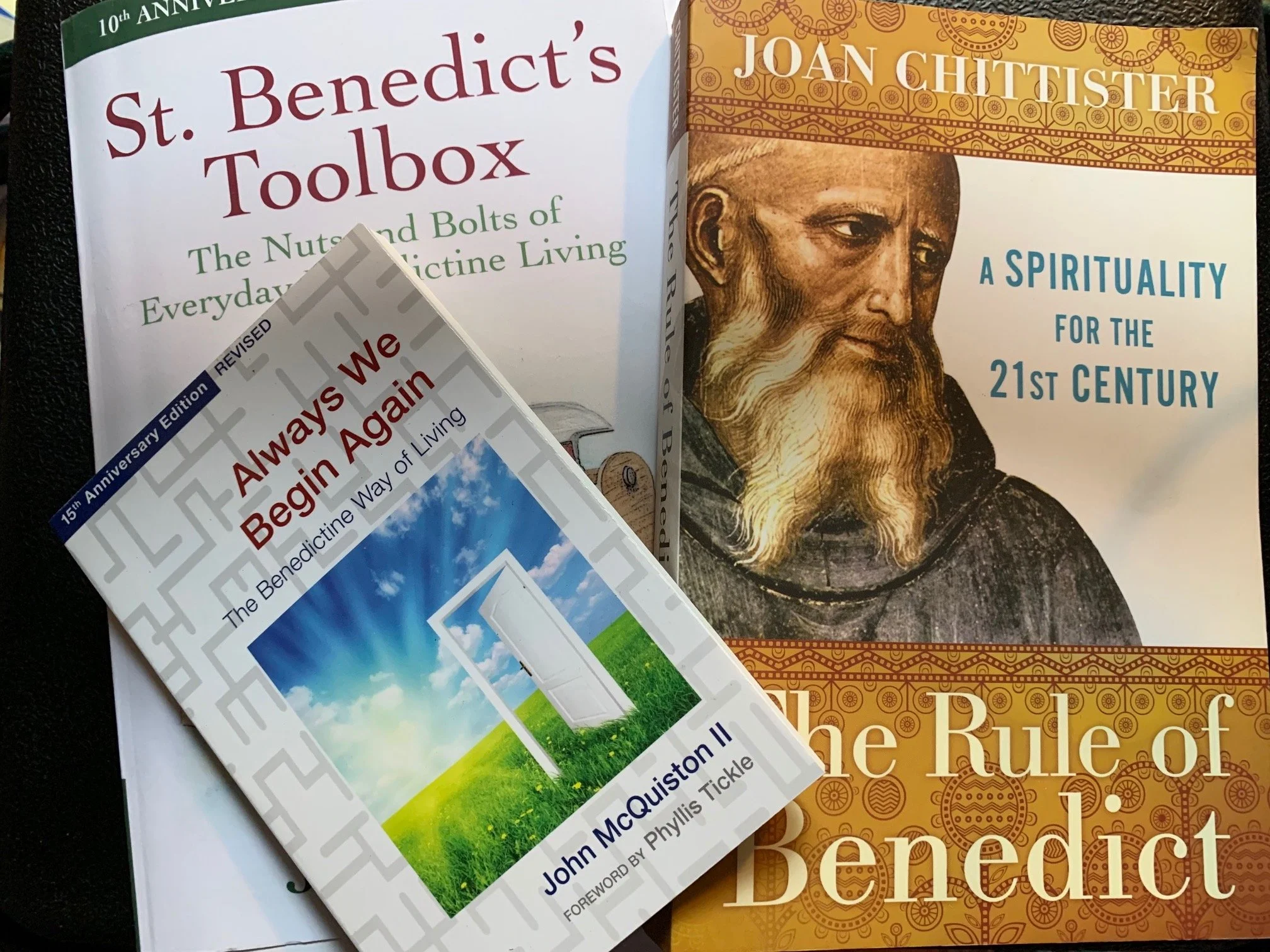

There are many outstanding books about the Rule of Benedict. I will share three favorites, but I would like to hear from others about the books that have been most helpful as you try to find your rule of life.

The Rule of Benedict, A Spirituality for the 21st Century, by Joan Chittister, is used by the International Community of Hope to train lay pastoral caregivers, immersing them in Benedictine spirituality. Joan Chittister writes a short meditation after each part of the rule and applies it to everyday life.

Always We Begin Again, The Benedictine Way of Living is a pocket-sized book someone can carry daily. Memphis lawyer John McQuiston II wrote this modernization of Benedict’s Rule and included a sample rule of life.

St. Benedict’s Toolbox is precisely what the author, Jane Tomaine, calls it in her subtitle, The Nuts and Bolts of Everyday Benedictine Living.

All three books are outstanding to read together in community, learning and supporting each other.

Joanna https://www.joannaseibert.com/