De Mello: Intercessory Prayer, The Empty Chair

“It is extremely important that you become aware of Jesus and get in touch with him at the beginning of your intercessory prayer. Otherwise, your intercession is in danger of becoming not prayer, but an exercise of remembering people. The danger is that your attention will be focused only on the people you are praying for, and not on God.”—Anthony de Mello in Sadhana: A Way to God (Image Books), p. 126.

Empty Chair

De Mello’s book had a significant impact on my spiritual practices. The awareness exercises of my surroundings, my body, and my senses have been the most practical avenues for learning how to experience God’s presence. I knew of these exercises before and tried them without success, but they now have become an essential spiritual practice for me.

One more lesson to remember: Spiritual practices that were not meaningful in the past can become important later.

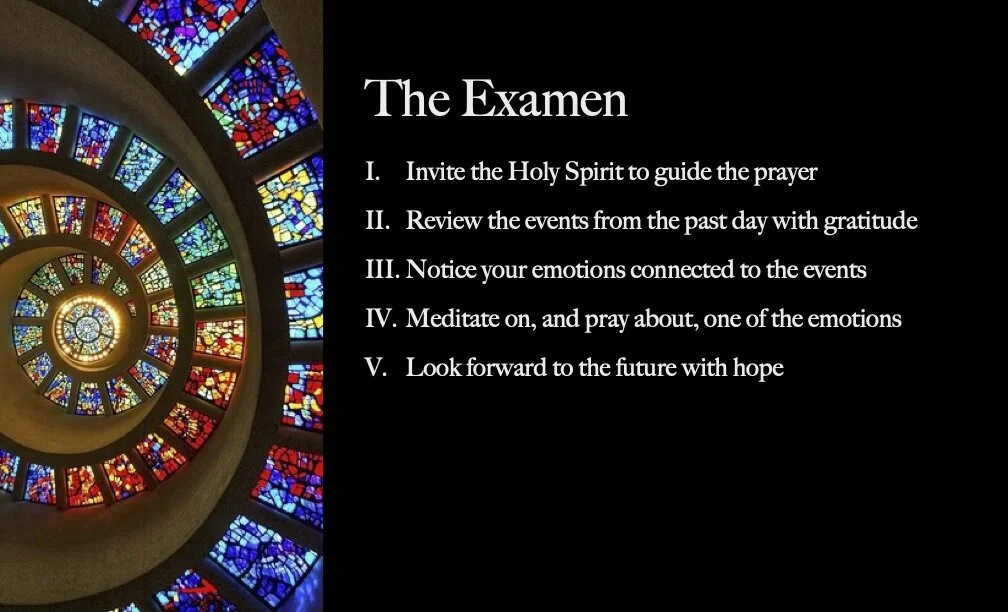

De Mello suggests that rather than envisioning the face or clothes of Jesus, we might seek a sense of Jesus in the shadows, calling him by as many names as we are led to. He recommends imagining Jesus in our prayers in an empty chair beside us. This can be one of the most consistent ways to experience the presence of Christ.

These intercessory prayer exercises can change how we pray and talk about prayer to others. We remember Jesus as the great intercessor, imagining Jesus’ presence directly beside us and visualizing those we pray for with Jesus laying hands on them.

The book’s last prayers deal with turning desires and prayers over to God one at a time—praising God at all times for everything, good and bad. This can also change our prayer practice and how we live our lives.

De Mello invites us to live and pray intimately, becoming part of the grand mystery of God’s love for us and all creation in the present moment. He believes this precious now, the present moment, is where God meets us.